Seas that Make Deserts

A Sea Changed, Part 6. Theme song by Band of Horses. Many deserts were once big lakes.

See here for the rest of the series about the Aral Sea precedent and people’s stories.

Next week we’ll see the dovetail and final part of this series — so named because the part will dovetail into a later series. The week after next, the Prelude part of the new series on AI and its more fundamental consequences will be released.

Today’s theme song is “The Great Salt Lake”, supplied by Band of Horses.

At 5am on a late summer day, I was startled out of my sleep in Salt Lake City, Utah. A sprinkler under the window of my Airbnb gave out a loud thump, and began spattering water onto manicured lawns and curated flowers.

A salt lake. A city. Sounds familiar. But what exactly? Still rubbing my eyes, I asked myself a question. 38 hours later — including 14 hours on the road between Idaho and Utah — I finally uncovered the answer, from a decade-old memory.

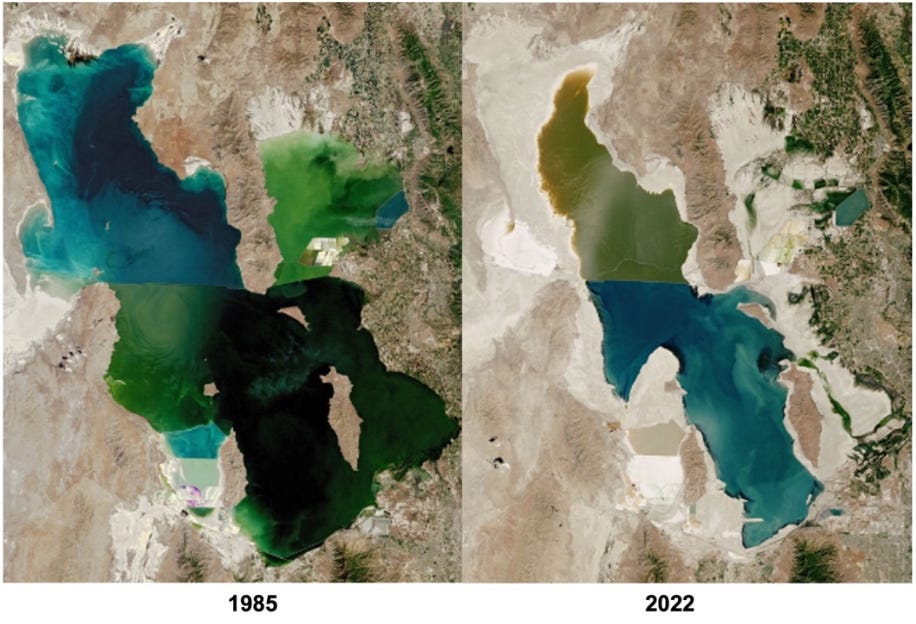

8,000 miles apart, the Great Salt Lake and the Aral sea are both saltwater lakes, and Salt Lake City is a much grander version of Muynak’s heydays. The two lakes even share the same fate: like the Aral sea, the Great Salt Lake has been drying up. In 40 years, a combination of drought and water overuse, has shrunk the Great Salt Lake to less than ⅓ of its former size.

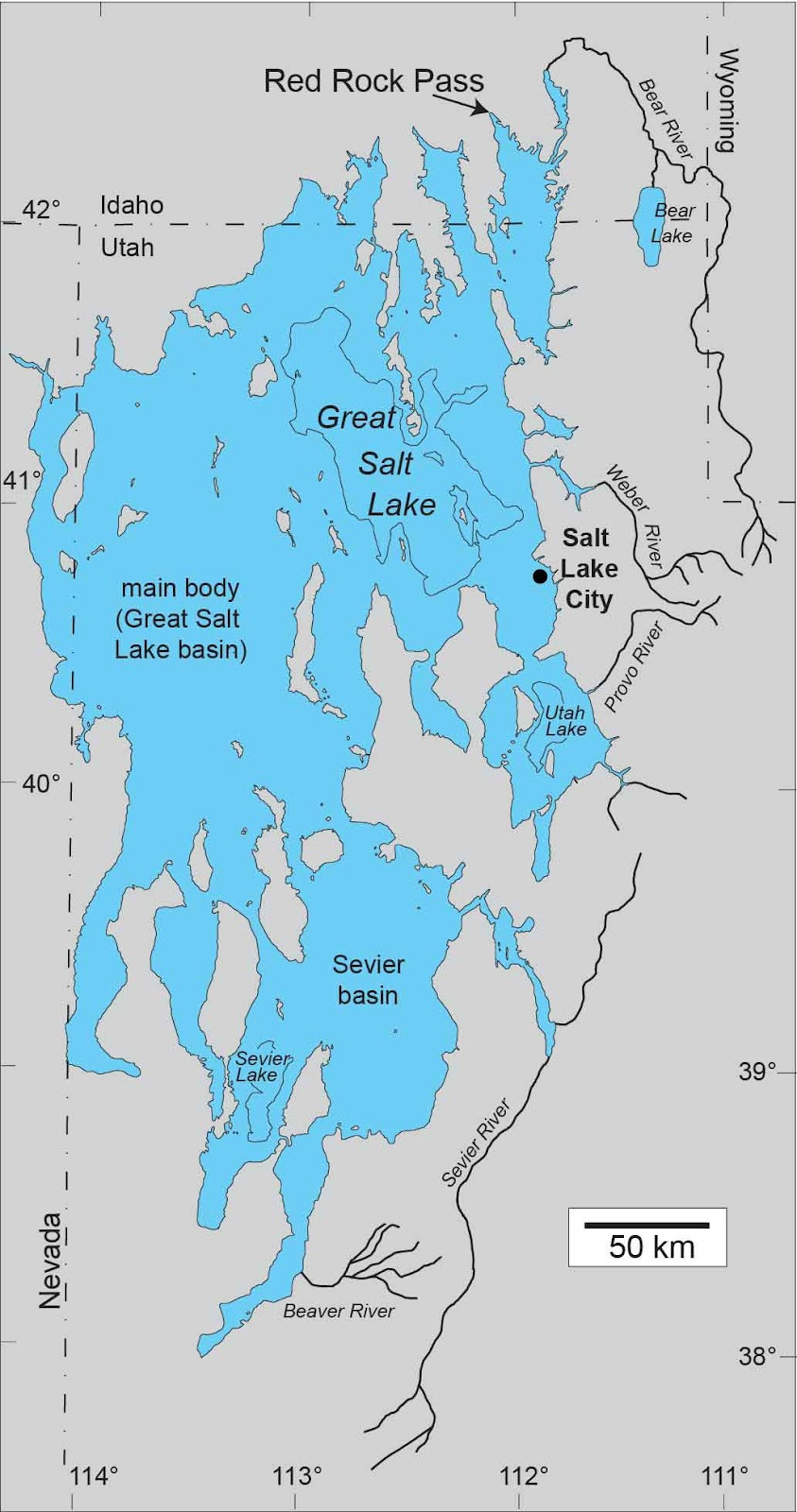

The Salt Lake is indeed great: it’s the world’s 8th largest lake, and the largest saltwater lake in the entire western hemisphere. Greater still, from rivers that flow into the lake, freshwater is drawn to sustain the state of Utah – a desert by all practical measures.

I suppose that’s why Brigham Young told his Mormon followers that the valley near the lake was “the right place [to settle]”: there is plenty of freshwater nearby.

Predictably, everyone hopped on the water wagon. Since the 1900s, more and more water has been diverted away from the three rivers that feed into the Great Salt Lake. Since around 2019, less than ⅓ of the lake’s natural inflow actually made it to the lake.

The other ⅔ went into alfalfa fields and golf courses, copper mines and food processors, power plants and fish hatcheries. Everyone gets a cut out of the lake’s freshwater supply.

From what I saw on my excursions, Utah’s canals and water channels are not nearly as leaky as the ones in Uzbekistan. But like the Aral sea, the Great Salt Lake hangs its life on a thin thread: water inflow and evaporation need to balance. Losing ⅔ of water inflow is cutting the thin thread bare.

Adding a multi-year drought that further cuts water inflow and speeds up evaporation, this life-or-death thread might as well snap already.

This is exactly what has happened. More than ⅔ of the Great Salt Lake – that is, about one-and-a-half Rhodes Island – has dried up. It left dust, salt, and arsenic-laced toxins in the lakebed. The water that remains, is 5X to 10X saltier than seawater.

We’ve seen this movie before: Drying of The Aral Sea has exactly the same plot.

But a force higher than all of us is also writing the plot. Around the world, saltwater lakes and other terminal lakes – lakes that don’t flow into seas or rivers – have been drying up or breaking up:

Owens Lake in California.

Mar Chiquita in Argentina, South America.

Lake Chad that straddles four countries in Africa, just south of the Sahara desert. Almost every continent has a big lake becoming a salt flat, a desert, and a supplier of dust and salt storms.

This phenomenon is not new. Until around 11,000 years ago, much of western Utah’s desert was covered by a lake 5X larger than today’s Great Salt Lake. The Great Salt Lake itself was among the last remnants of this prehistoric greater lake.

Death Valley is another example. Its deserts and salt flats were under water of a large lake, when Neanderthals still roamed around. Between then and about 10,000 years ago — roughly a quarter million years — the lake disappeared and returned several times, before finally yielding to the deserts that became Death Valley.

There is only one problem: this lake-desert cycle used to take thousands of years to happen. Now it’s done in half a century or less. 90% of the Ireland-sized Aral Sea was lost in 50 years. In 40 years, 2/3 of the Great Salt Lake dried up. 95% of Lake Chad, which had been bigger than the state of Oregon, was gone in 35 years.

*****

On a trail high above the Great Salt Lake’s dark blue surface, the air was still stinky. But I hiked on. What I saw could be the last stand of a great lake — this realization brought a strange sensation to me. Thousands of years of natural changes are compressed into the lifespan of one human: isn’t it the most thrilling for us to witness such drastic changes in our short lives?

It’s also scary. So much change, so little time, and so many human lives at stake. How will nature respond? What’s the price we’ll pay? How are we going to cope? We do not know.

But one thing is for certain: thrilling or scary, we live with and struggle against forces of nature all the time. Sometimes we triumph, sometimes we fail; other times we screw up, and pay a heavy price; yet another time we get things just right.

I looked at the Great Salt Lake one last time from the ridge, and started descending the trail. That evening, I would ride a train westward bound, through sequoia woods and cedar forests, by streams and brooks, over canyons and valleys, towards another night’s moon and a new day’s sun.

Thank you for reading Earthly Fortunes. If you like it, please share it. Subscribe for free to join me on journeys into the once and future seas, deserts, and other random places.

Let me know your thoughts in an email reply, in the comments, or DM me on Twitter or Instagram!

I am vicariously having these experiences and emotions through your writing. More power to you, bring us more earthly fortunes.

"Thousands of years of natural changes are compressed into the lifespan of one human: isn’t it the most thrilling for us to witness such drastic changes in our short lives?"

yeah, that's a heavy thought lol