This is part 1 of the series A Sea Changed. See part 2 for a fisherman’s life in the desert, part 3 for white gold (or, the snowballing of solutions into big problems), part 4 for a T. S. Eliot quote, a theme song by Tom Lehrer, among other things, part 5 for candy and vodka.

My photography skills are rather sorry, and significantly worse many years ago with much lesser equipment and zero forethought. So I’ll direct you to photos from hands far more competent than my own.

Have you ever been caught in a salt storm? I have, next to a lake that was supposed to be as big as Ireland. A yellow wind swept up, and the next moment I felt someone was smothering me over my nose and mouth, because no air was coming in. It was all salt, sand, and urea that I inhaled. I wriggled about, jerked my head back, and slammed the door with a bang that the whole house could hear, all before submitting to violent coughs and chugging every drop of drinkable water.

The next day, after the sky cleared to blue and storm subdued to breeze, I cleaned the house and the yards with my host family. That Lada Niva off-road vehicle was treated to damp rags that wiped off the wind shields, windows, mirrors, and lights; most dust and salt on its grey-ish green body were left untouched.

Soon, I’d take that Niva into the desert, located next to this town I was staying at. In the desert, I’d camp by the remains of sunken ships and abandoned boats.

I was in Muynak, Uzbekistan, a landlocked country in central Asia, about the size of Sweden but has more than 3X the population. From Muynak, the closest ocean is about 1,300 miles (~2,100 kilometers) away — long enough for you to fly from Orlando, FL where a long sleeve jacket counts as winter clothing, to Minneapolis, MN where street lights are buried in snowbanks for Christmas.

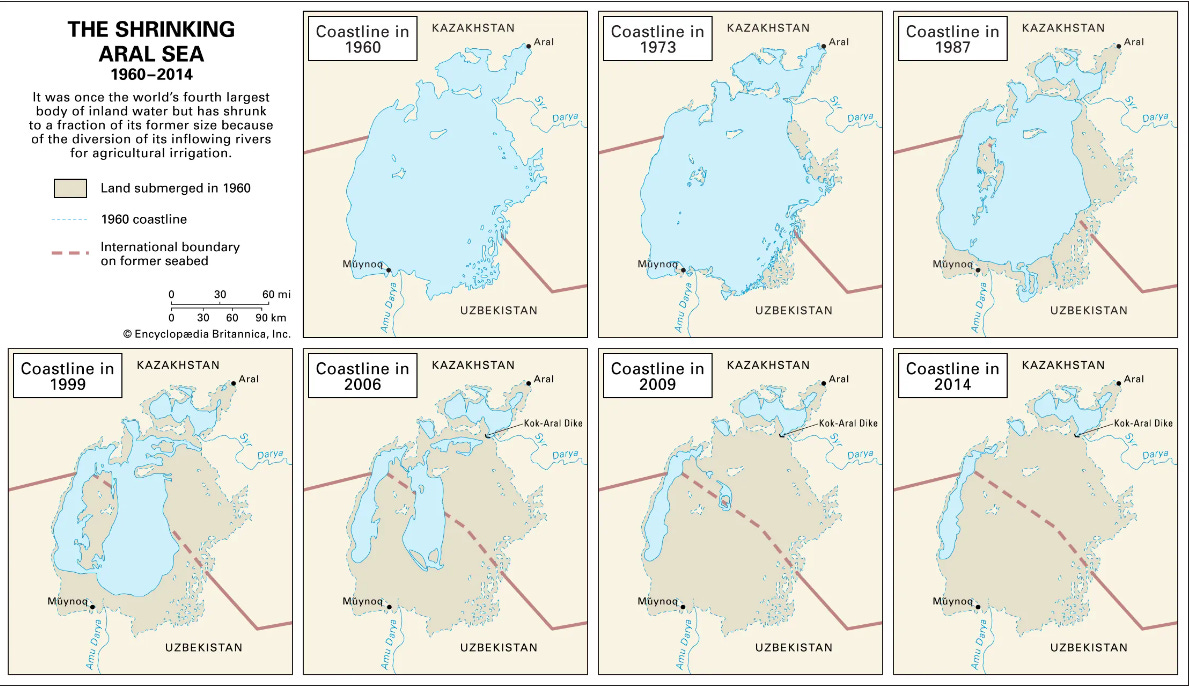

50 years ago, Muynak sat by the world’s fourth largest lake — a lake as big as Ireland — and bustled with tens of thousands of people in fishing, meat processing, and transportation. My host family always grinned when recalling their childhood: in the lake, they competed in swimming, rowed boats, and caught fish for their meals.

The day of the salt storm, Muynaq sat by a desert, was 55 miles (~90 kilometers) from salty lake water, and perhaps only a thousand or so older folks remained.

Muynak did not move an inch, it was the lake that retreated, dried up, and left salt, sand, and urea on its former seabed. Because the lake is not a lake anymore, the lake’s name changed, too. From Aral sea to Aral-kum — “kum” meaning “sand” in several central Asian languages — it took fewer than 50 years to happen.

Many will entertain you with a quick how-it-happened-and-whodunnit story:

Back when central Asian countries were parts of the Soviet Union, a plan was drawn up in the 1950s: canals would be built to divert water from the two major rivers that feed into the Aral sea, to irrigate fields of cotton and other crops elsewhere. These crops would be exported to make money and grow the economy. Soon, the irrigation plan was implemented. As water inflow disappeared but outflow persisted, Aral sea started to dry up. Year by year, the lake retreated further, leaving sand, rocks, and salt in its seabed. 50 years later, the lake was a 10% shadow of its former self; even this remaining 10% was split into two shrinking bodies of ever saltier water.

The story has a tragic veneer, and prompted me to come to Muynak in the first place. As the Niva wheezed and burst into the desert like a midnight city bus on empty streets, I felt something was missing from the story.

It’s easy to smirk and conclude that the Aral sea disaster was made by the [insert your favorite negative adjective here] Soviet policy, then move on and over. It’s hard to look beyond the narrative, and ask:

Could similar things happen elsewhere? If so, how?

What are the lessons we can learn? Is it “don’t build irrigation”? Is it “don’t grow cotton”? Is it “don’t change nature” with qualifiers? Is it something else?

Aral-kum was made, now what? Is there a chance to improve the status quo? How?

Does the Aral sea story really end there?

“Look — ships,” my travel companion said, pointing to rusty wrecks of two fishing boats resting bow to stern, on bright sand waves among pale green shrubs.

There they were, ships and boats in their desert graveyards. They lay still, like whales washed up on beaches, but not even trying to maneuver away from the sand, or calling for protections from storms. Their hulls let their bare ribs hang out in the dust. Their keels floated in sand waves, but nobody was at rudder to steer or on deck to fish. Having no sailor to protect from falling overboard, their bulwarks idled.

I acknowledged my travel companion’s observation, and looked for a large ship, next to which I’d set up camp.

Unbeknownst to neither of us, we were heading into an evening of most unexpected encounters.

Thank you for reading Earthly Fortunes. If you like it, please share it. Subscribe for free to hear more about how the Aral sea changed and what we could learn.

Let me know your thoughts and questions in the comments or DM me on Twitter!

Echoing Sandra and loving how visual your writing is. I love how you're mixing history about this place and your personal adventure within this place! Excited to re-read this series =]

"There they were, ships and boats in their desert graveyards. They lay still, like whales washed up on beaches, but not even trying to maneuver away from the sand, or calling for protections from storms. Their hulls let their bare ribs hang out in the dust. "

Helen, I love the imagery in this. I dig the spooky ship desert graveyard. Thank you for sharing!