As promised, this 24th issue for March 24th 2023 is a Special Edition. Dedicated to the memory and legacy of M.B.. Artist extraordinaire, maverick, philosopher, pioneer, teacher, friend. Happy would-be birthday.

Today’s theme song is Verwandlungsmusik (transformation music) from the opera Parsifal, composed by Richard Wagner. Recorded in 1964, conducted by Hans Knappertsbusch.

I wish I had taken his pictures there in the kitchen, sitting upright and erect in a bare chair at the table, poking a spoon and a fork into his salad bowl as though he were counting rhythms for the fridge’s electrical humming. At high noon, when I hiked half an hour up the mountain and hauled my copy of Parsifal into his kitchen, Marc was at his most relaxed. The sun opposite me shone on Jean-Jacques, clad in a loose apron atop a red shirt, shuttling between the stove, the fridge, the storage, and the table.

“There is too much oil in the salad,” Marc said. He took a bite of the colorful salad, put down the fork and the spoon, and pushed the bowl away. Flowing shadows in the kitchen silhouetted his perked-up ears, sharp eyebrows, and threads of remaining silver hair against a pristine wall and a clock.

Before I could properly “salut!” either of them, Jean-Jacques tilted his head to the door, and called me out:

“Mademoiselle – can you tell Master to eat more salad, please? Salad is good for his health.” He enunciated slowly.

My lungs were still gasping for air after the hike, but I complied. “Monsieur, Jean-Jacques told me to tell you to eat more salad. He said salad is good for your health.”

It wasn't until much later when I realized this: Jean-Jacques never called Marc by his name. True to his professional butler training, Jean-Jacques always addressed his employer of more than 40 years as Master. When I asked him about this, Jean-Jacques remarked that I should be calling Marc "Master" too – because Marc was the master musician, and I his apprentice.

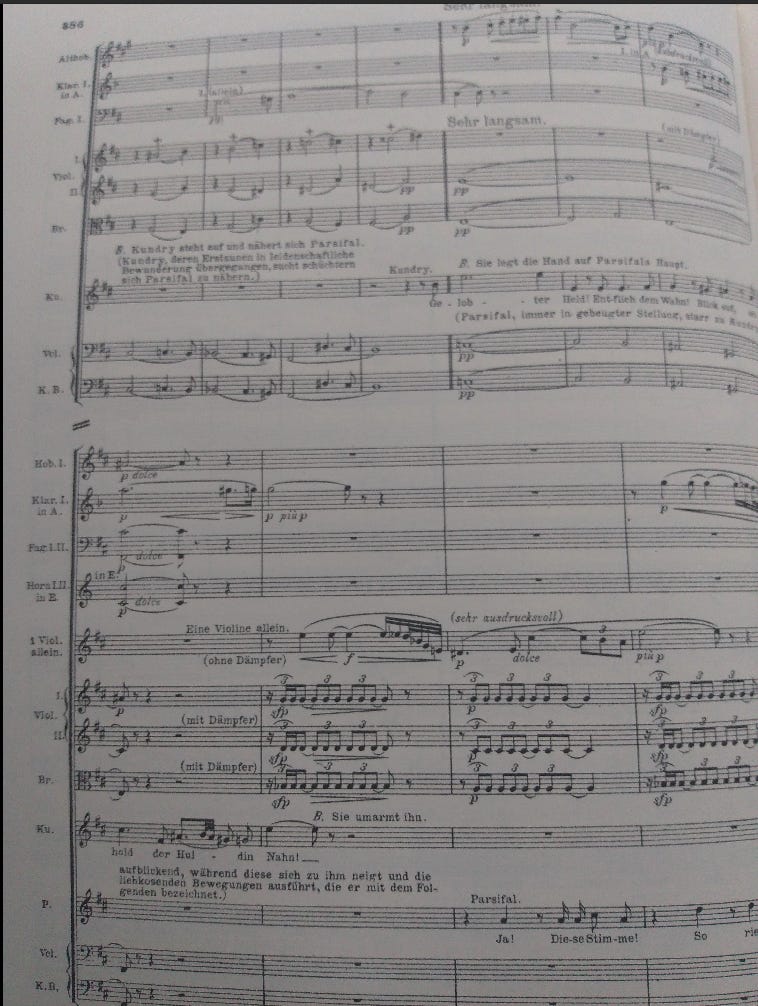

Back there and then, I had no time to contemplate such finer points. I plopped into the chair next to Marc, pushed away the salad bowl further, and gingerly laid my copy of Parsifal on the table. 600 pages of orchestral music score made a muffled sound on contact with the plain wood surface, and I opened to a page already half-covered in pencil-scribbles. Some harmonies and orchestrations in the score befuddled me, and I needed Marc’s help.

Wagner’s Parsifal is one of the most complex operas ever written, and cracking the music’s mystery is never supposed to be easy. It only looked easy, when Marc did it.

His fingers glided over the staffs and notes, pinpointing vertical structures, horizontal lines, phrases, chromatic shifts, timbres, subtle color changes, modified motifs, among many other things I had thought I knew, but just ain’t so. His terse commentaries flew at rapid-fire speed, piercing through the hearts of all my questions and confusions across many pages. My pencil could barely keep up with the enlightenment streaming into my ears.

Many musicians assert their energy by wild movements and grandiose contortions. Such is not the case with Marc. He never stomped, wiggled, swung sideways, or made any unnecessary gestures to explain the music. “Correct, bassoons can mess up the rhythms here. It’s ya-da-da-da…” he’d say, while moving only a forearm up, down, and sideways to count beats at thorniest moments of the music, as if I were an entire orchestra at rehearsal.

Even when I asked stupid questions, he never raised his voice or rolled his eyes ever so slightly. Instead, he’d lean back in the chair, put his fingers to his chin as if praying, and open his gray eyes so wide that they seemed to jump into mine, to discover mine had not paid enough attention to the score, to notice things I should have noticed. Maybe his brief gaze could conduct electricity to activate my music brain – before long, on my own, I’d have righted my wrongs, and he would utter a syllable of approval, then spring back up to keep reading the score with me.

Sometimes I wondered what he would do, if I returned the same pensive gaze to him – would he burst out laughing, or ensue a staring contest with me?

A staring contest may amuse an onlooker. Imagine this: a shaggy-haired young woman in a wrinkled windbreaker, and a svelte octogenarian gentleman in a neatly pressed gray blazer, sitting at a kitchen table, and staring at each other over a door-stopper of music score next to a salad bowl – Jean-Jacques would have cackled for days about this.

The contest never happened. Instead of laughing his heart out, Jean-Jacques would put a basket of bread on the table and disappear from the kitchen, leaving only Marc and me there. When all notes, rhythms, and structures leapt off the pages to make sounds in my mind, it was time to move to the piano. I’d play through a reduction of the orchestral score, and sing certain parts at the same time.

My pianistic skills were – and still are – rather modest, so I won’t bother you with the details of holding tempo, staying accurate, maintaining clarity, and coordinating my eyes, hands, ears, and tongue. Curiously, Marc thought my modest skills were an advantage. Because you have to play music with your mind, not with your fingers, he said.

The only thing that matters in a piano reduction, according to Marc, is knowing what’s important in the orchestral music and what’s not, so you play only the important parts on the piano.

Indeed, every time I tried to play meaty Liszt-style chords, or make a rubato on the Bösendorfer grand piano, he always tapped on my shoulder to stop me from sliding further into the dark side of musical forces. Then a blitz-quiz would stream from him, based on our studies in the kitchen. What are the most important chords in this segment? Could you do the same with fewer notes? Let’s try this: can you play these four measures with two fingers only? What could go wrong with the rhythms? What’s the complexity you can cut? What’s the simplest, the most essential musical information you need to keep?

And it worked. His incisive attention and understated energy did make me think deeper, play with more focus, and try harder at the piano. Every time when I played through without a shoulder tap, he’d smile and give me an approving nod – and then I’d feel I was Luke Skywalker, and Yoda just told me, a great Jedi you shall become.

When I told Jean-Jacques that Marc was Yoda, I was his Jedi-apprentice but in music, Jean-Jacques objected to my American-influenced view of his Master. Loyal to his European roots, he insisted: Marc was Hans Sachs, the revered but aging Meistersinger1 of 16th-century Nürnberg, and I was the young poet-knight Walter who sought his Master’s wisdom in art.

Wherever Master is, there is music, there is art. Jean-Jacques sputtered, in adoration. Talking about his employer of more than 40 years, this elegant septuagenarian sounded like a teenage boy gushing over his favorite soccer player at Real Madrid.

Many smart people say no man could be a hero to his valet. Marc proved them all wrong.

And to me, Marc was the most generous teacher, always ready to impart his knowledge and wisdom. But about town, there was always a mythical and somewhat dark reputation around him. Be careful, young lady, I was warned by stern tongues, your teacher might have sold his soul to the devil, in exchange for those keen ears and clear eyes at his age.

I didn’t know how to respond to these rumors. Marc might be my music master and I his apprentice, but we never had any formal agreement — so if he had really made a deal with the devil, the deal would not have passed down to me anyway. Every week, I hiked up through the forest to his house, sometimes twice, sometimes five or six times, and even when he was out, I was allowed to play the Bösendorfer grand, to fine-tune my ears, and to make sense of any orchestral score I was studying.

He refused to accept any payment at all. But he did make me promise that I would work absolutely the hardest, to the best of my capabilities, and give my all to music.

Serve the music. Serve the art. Serve no man. He commanded, from the kitchen table, like king Arthur summoning the knight Galahad to go on a quest for the Holy Grail.

I understand. I will do. I replied, bowing my head in affirmation. A ray of sunlight shone into my eyes, and dazzled me for a second.

Then I saw him smile. His grin on the wrinkled face was so wide that I was afraid it would devour his ears, and he would have to teach music from memory — like Beethoven once did.

“Very well. So you want to study Parsifal?” He said.

Music, when soft voices die,

Vibrates in the memory—

Odours, when sweet violets sicken,

Live within the sense they quicken.

(Percy Shelley)

Who are the most influential teachers in your life? How did they transform you? Let me know your thoughts in the comments, DM me on Twitter or Instagram, or just reply to the email!

Thank you for reading Earthly Fortunes! Like it? Please share it! 😄 Subscribe for free to hear more about the earthly fortunes: time, dovetails, variety of life, and the Unseen of AI.

Composers of art songs and lyrical poetry in medieval German cities.

This is a remarkable piece, Helen. An absolute delight to read and enjoy. It's funny how we spoke for nearly two hours upon our first encounter and barely spoke about music.

This is an amazing account well told! Oddly enough, I find it reminiscent of Patrick Rothfuss' Name Of The Wind and how he depicts the studentship of the keenly apt protagonist Kvothe.

It certainly hits upon the archetype of the sage and student.

I dream of writing like this. Beautiful. Silvio said everything I started to say ...