Laws of Art (and AI)

Quid ex Machina, Act I Scene 1. Theme song by “Weird Al” Yankovic. Do you really want to find out?

This is the 2nd essay of the series Quid ex Machina, which examines the deep, under-explored, and Unseen impact of AI on humans and our societies. See here for the rest of the series.

Today’s theme song is Pac-Man by "Weird Al" Yankovic, an eminent artist of transformative works. The song is a parody of Taxman by The Beatles.

“Do you really want to find out?”

This is a favorite question of copyright lawyers. I ran a niche indie publisher for almost a decade, so I heard this question plenty, and grew strangely fond of it. So fond that for years, I’ve dug into the history of copyright, and followed copyright sagas from 50 Shades to Blurred Lines and beyond.

Now that I’ve been working in AI research, this question is still near the top of my mind. The only correct answer to this question, by the way, should always be a firm “No”. Because you really don’t want to find out how much damages you’d pay for potential copyright infringement lawsuits.

So, in 2022, when AI image-generators (Midjourney, Stability AI, and later DeviantArt’s DreamUp) rushed to the market, my immediate reaction was not one of warm praise (it came after), but of morbid curiosity:

“Copyrighted images were definitely used in training. Maybe someone really wants to find out.”

My premonition materialized, when several artists (Andersen et al) and GettyImages sued AI image-generators for copyright infringement1. And I was surprised by the number of opinions that show a shocking lack of research, personal experience, or any knowledge about copyright law.

In this essay, I’ll address questions around copyright and AI image-generators. This is also my starting place to inquire into AI’s larger, Unseen impact on humans and our societies.

Copyright is as complex and messy as human creativity, so let me know if I didn’t make things clear enough.

I am not a lawyer. Nothing here is legal opinion or advice, or should be construed as such. Everything is based on my personal experience, research, and consultations with experts. This essay is for information and entertainment purposes only. Take everything I say with a pinch of salt.

Do you want to find out about copyright laws of art and AI? Let’s dive in.

Copyright: A (very) Brief History, from pre-Gutenberg to post-Google

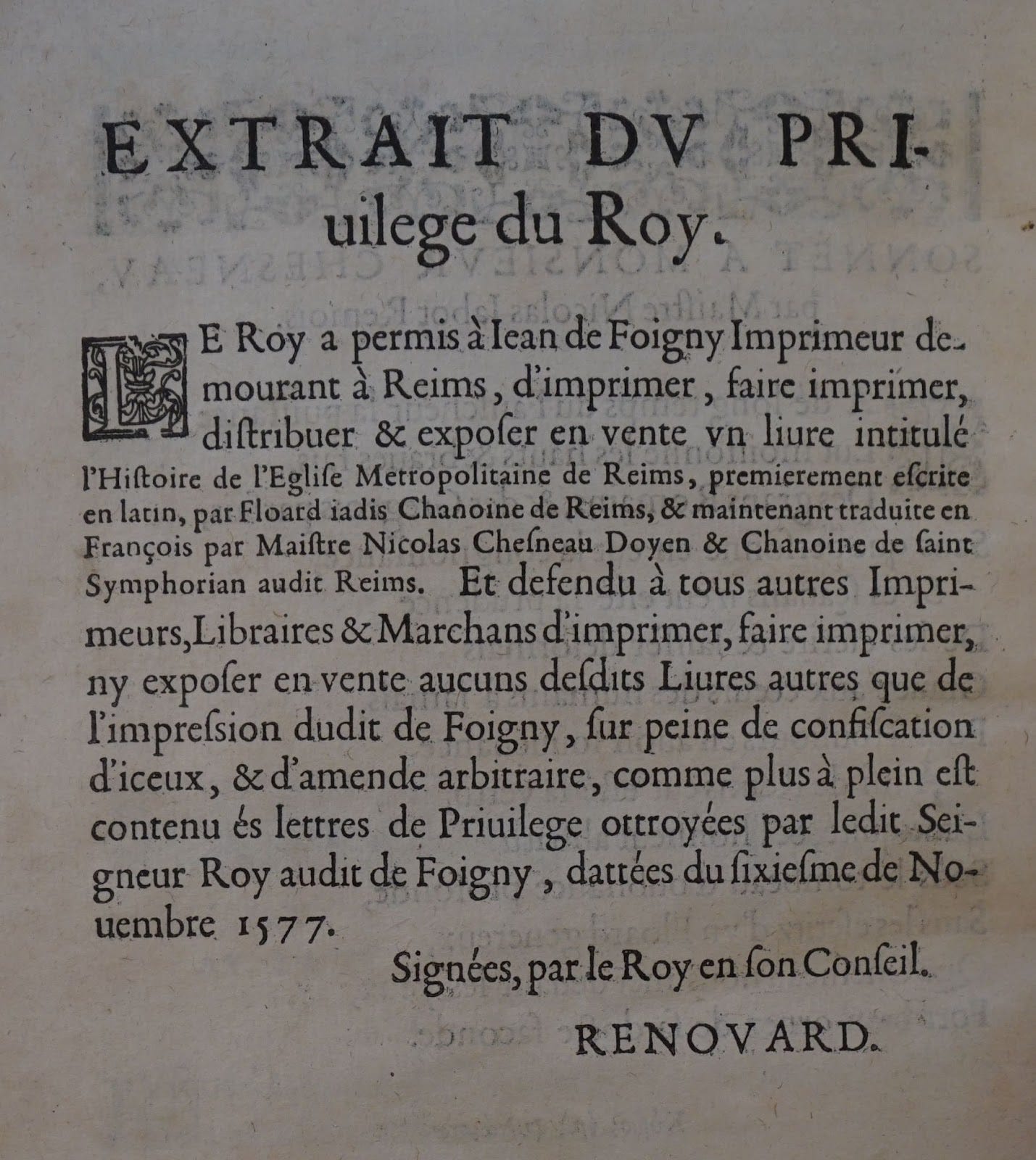

Many years ago, when I started my niche indie press, I didn’t need to schmooze for a royal license. But when copyright started to emerge 500 years ago, it was all about royal favors. Back then, royal privileges and licenses were doled out by European monarchs to their favorite artists and publishers. No one else but the Chosen Artists were allowed to publish and distribute works of art. These publishers’ exclusive rights to print and make copies, came to be known as “copyright”.

Royally appointed publishers monopolized printing activities. They also enforced censorship standards on all publications, and were on the hook for their behaviors. You published heresy or sedition? Jail time or the stakes for you.

Censorship and monopolies on printing – these were what copyright was meant for. Copyright was also a private right of publishers, not a public grant available to everyone.

Until Gutenberg’s printing press got extremely popular after the mid-1500s. Suddenly, any priest or craftsman or gentle folk who got their hands on a press could print anything they liked. Royally appointed censor-publishers couldn’t keep up with printed seditions and heresies anymore. With John Milton supporting the “liberty of unlicensed printing,” followed by 30-year-long disputes between English and Scottish publishers over who could print what and be sold for how much, finally, the Copyright Act of 1710 passed in England. It was the first law that made copyright a right of authors.

Because the 1710 English law didn’t apply to the American Colonies, the U.S. had a late start in copyright. At James Madison’s proposal, the Copyright Clause was written into the U.S. Constitution.

[The Congress shall have Power…] To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.

(U.S. Constitution, Article I, Section 8, Clause 8, known as the Copyright Clause. Source. Emphasis by the author.)

But the 18th century had no TVs, movies, music recordings, photography, software, or the Internet. After 200+ years of legislations and litigations, two cases – both featuring Google — provided major legal precedents for copyright in the 21st century.

We all love Google Image search; the thumbnails are handy. One exception: the publisher of Perfect 10 (“P10”), a magazine — as I was told — “more risqué than Playboy and Penthouse”. In 2006, P10 sued Google for copyright infringement, because Google indexed the magazine’s covers, and displayed their thumbnails in searches.

(If next week my Google top results become sponsored ads by Playboy or Penthouse, I’ll know why.)

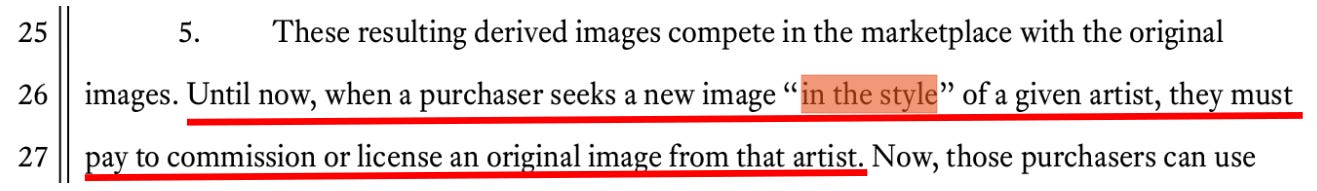

In 2015, Authors Guild sued Google for copyright infringement. This time because Google scanned library books (some still copyrighted), and provided snippet views as search results.

In both cases, Courts ruled that Google’s use of images and snippet texts was highly “transformative” and constituted fair use, so did not infringe copyright of either P10 or Authors Guild. For P10, the judge wrote:

"...the significantly transformative nature of Google's search engine, particularly in light of its public benefit, outweighs Google's superseding and commercial uses of the thumbnails in this case.”

(Judge Ikuta, Perfect 10 vs Google, 2007. Emphasis by the author.)

Or, in the case of Authors Guild, despite Google’s unauthorized scanning of copyrighted works, the scanning was intended to enable search, and search is a transformative, fair use of copyrighted materials. Hear it from the Judge:

“...Google’s making of a digital copy to provide a search function is a transformative use,

which augments public knowledge by making available information…”(Judge Leval, Authors Guild vs Google, 2015. Emphasis by the author.)

Transformative. Fair Use. These two concepts have been at the center of many copyright lawsuits in the last 30 years. The current lawsuits around AI image-generators, and the future of artistic expression hinge on these two concepts as well.

But what counts as “transformative”, and what makes for “fair use”? In what ways do they matter for Getty Images vs Stability AI and Andersen et al vs Stability AI et al?

Now we are getting closer to the heart of matter.

Transformers

In my eyes as a publisher, 50 Shades of Grey and the Book of Mormon are the same: they are both transformative works. They built on someone else’s creation, added new things, with further purposes, and in different manners. 50 Shades is an adult’s smutty re-telling of the chaste teen romance Twilight. BoM used Jesus in the New Testament to found a new religion in the US.

Neither author paid a dime to that someone else who wrote the original work they built upon. But the reasons are different. The New Testament is in the public domain and has no copyright owner, you can use it as you wish, for free — write a religious text, make a neorealist film, compose a rock opera… anything goes. No heirs of St. Matthew would chase you down for a license fee or sue you for copyright infringement.

Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight is under copyright, but 50 Shades is so transformative of Twilight that it could be plausibly claimed as fair use; and Meyer might not have had a chance to win, if she sued for copyright infringement2.

Many parodies (e.g. today’s theme song), satires, criticism, commentaries, reviews, and fanfiction also count as transformative works of the original copyrighted works, so they don’t have to pay the original copyright owners either. In Google’s cases, search function as a purpose is transformative, and gives the public enough new information to be judged as fair use.

Beware though: how much transformation counts as sufficiently “transformative” to claim fair use is highly subjective. No bright line standard exists. You’ll need to find out at a court of law considering four factors, on a case-by-case basis. Although under Factor (1) and other legal precedents, the more “transformative” your new work is, the more likely your work is going to be seen as fair use.

But if nostalgia compels you to make a musical, ballet, or movie reboot etc. based on Twilight, before getting to work, you need to pay Meyer to get a license. This is because your dream projects are derivative works – they are based on preexisting Twilight books, adapting the books’ characters and stories to different mediums. Derivative works must be licensed from copyright owners of the preexisting works. Unauthorized derivative works are not fair use and liable to pay damages for copyright infringement, even if they don’t make money.

This is the heart of the lawsuits around AI image-generators:

Getty Images vs Stability AI says that the input to AI image-generators copied Getty’s images without permission, and some outputs are also derivative images of Getty’s originals. The class action Andersen et al vs Stability AI et al goes further to allege that all outputs by AI image-generators are derivative works of some copyrighted images. It would be copyright infringement all the way down.

In both cases, I anticipate that AI image-generators will argue that their inputs of copyrighted images are fair use, and their outputs are transformative works. Otherwise…Well, I don’t think lawyers of Stability AI, DeviantArt, and Midjourney really want to find out how tall cash piles can stack, when it comes to paying for copyright infringement damages.

There is still a 3rd keystone that our future of artistic expression hinges on, and one lawsuit is attacking it. If we – and the courts – are not careful, we could be ceding 500 years of progress on copyright.

Let’s dive deeper.

Future of Artistic Expression is at Stake

There is a one-and-half line from the class action’s claim:

This is the single most dangerous one-and-half liner I’ve seen, for the foundations of creativity and future of artistic expression. More dangerous than Disney’s lobbies, GettyImage’s copywrong claims, and Nintendo's litigious tantrums combined.

Why?

It’s wrong. It doesn’t square with how creativity happens in real life. It hurts the artists that the lawsuit tries to protect.

Art students copy “in the style” of great artists all the time, and never sought permission or paid for licenses (Nor should they!). So all art students infringed copyright then? No! That’s how artists learn, that’s how we all learn to develop skills and creativity.

I could go to my artist friend Pedro, and ask him to paint an image “in the style” of Andy Warhol, but on a completely different subject. If he did paint it – nothing happens. We didn’t infringe Warhol’s copyright.

I could try to copy Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe. But I’m so terrible that my copy turned out to be squiggly lines and contours of circles. Did I infringe copyright? No. My copy looks nothing like Warhol’s original.

In truth, in literature, in science and in art, there are, and can be, few, if any, things, which in an abstract sense, are strictly new and original throughout. Every book in literature, science and art, borrows, and must necessarily borrow, and use much which was well known and used before.”

(Justice Story, Emerson v. Davies, 1845.)

You don’t get copyright protection over a style. A style is an idea – like the concept of drinking water. An actual work of art, “…captured in sufficiently permanent medium”, is an expression of the idea – like finding your favorite mug, filling it from the tap, lifting it to your lips, and sip or chug the water. Say it with me: copyright protects expressions of ideas, not ideas themselves. This is the idea-expression divide in copyright law.

If copyright protected ideas, then whoever first came up with the style of Surrealist painting, could claim all Surrealist paintings that have ever been and will ever be as their own (fortunately, they can’t). Copyrighting the concept of drinking water wouldn’t be far off, either. Then we’d have to pay royalty fees every time we drink water: because this basic human need for survival is an expression of someone’s copyrighted idea, and since we used the idea, we are liable to payments.

What a dystopian world it would be. In that world, copyright would not “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts” any more. It would regress to its original form 500 years ago, a way for the few Chosen Artists who “own” ideas to create monopolies, to lay claims to any creations past, present, and future that has a trace of their “ideas'', and to enforce their favorite forms of censorship. The rest of creators would be left starving, without legal means to publish and distribute their work.

If the court accepted this claim, the future of artistic expression and creativity would be dark. Everything we could ever do would infringe on someone’s copyright, making it impossible for us to borrow and to build on other people’s works.

My ambitious friends often tell me about their plans to change organization rules they don’t like. When they ask for my opinions, I always say: “Do anything you want. Just remember that the rules you make, can be used against you by your worst enemy too.” In Andersen et al vs Stability AI et al, the artists could prevail on this “style” claim, but the new ruling could be easily used against them. Other artists may claim that their styles were copied without a license by Andersen et al, and seek damages. Those cases might have nothing to do with AI, but still hurt artists worse than AI image-generators ever could.

I wish I could say that judges are unlikely to rule in Andersen et al’s favor, but a recent high-profile music copyright case upheld a similar infringement claim. A jury ruled that the songwriters of “Blurred Lines” must pay more than $5 million of damages, for allegedly copying the “feel” of a Marvin Gaye song — even the the lyrics and melody differed. I knew of no musician or copyright lawyer who had thought the verdict would go this way, but alas, it still happened.

Are you ready for a world where you pay royalty fees every time you drink water? Do you really want to find out? This is the stake.

On the Other Hand

I don’t run the indie publisher anymore, but I love and respect artists all the same. I criticized the artists’ dangerous claim, but I also see their frustration and anger.

Should AI image-generators have sought permissions from copyrights-holders before using the data to train AI models? I think so3.

Midjourney’s CEO claimed that “there are no laws specifically about [harnessing copyrighted images for training]’. Is this claim disingenuous and lame? I think so too. Just because something is on the Internet, doesn’t mean that you can use that something however you like. Works under Creative Commons licenses require attributions to the original creators4. If you remix deadmau5’s music from YouTube with Beyonce’s tracks from Spotify, you need to get proper licenses before releasing the remix as your own. Otherwise…Do you really want to find out?

Sure, scrapping publicly available data on the internet is not illegal, but whether you can use the scrapped data to train AI models remains an open question.

And “an open question” does not mean “do what you want, without consequences happening to you”. Now the courts must decide if the whole operation is legal to begin with, and if using publicly available, copyrighted data to train AI is fair use.

Should AI image-generators attribute their images to artists and their artworks? Absolutely. Artists make a name by getting attributions from others; attributing the sources of AI-generated images is both an acknowledgement of human creativity that enables AI, and an amplifier to the artists’ craft and reputation. A 3rd-party tool is already doing this, and every AI image-generator should do it too. It’s an act of good faith. It’s an act of connecting us to the human behind the machine.

Should AI-generated images without human modifications stay in the public domain, without any copyright, so that everyone can freely use them for any purpose? Absolutely. Copyright protects creativity, and human agency is required of creativity. Needless to say, machines and algorithms are not humans and have no agency to start being creative.

Where Law Ends and Art Begins

What Guterberg’s technology did to put printing power in the hands of the public, I foresee AI image-generators will do too. All the AI tools are broiling in legal and ethical hot seats now, but the cat is out of the bag: the tools are here to stay. They will unleash profound social changes and help us unlock more creative forms.

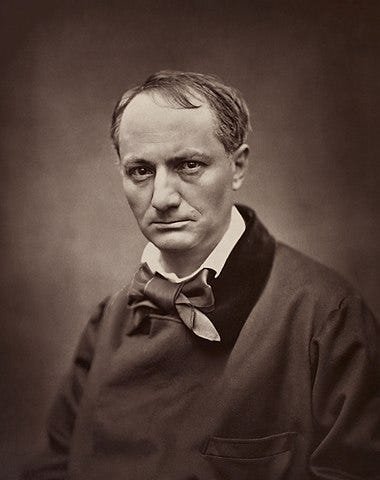

If neither reality or law could soothe your anxiety, history offers another comforting precedent. In 1859, the French poet Charles Baudelaire lamented about photography:

“[T]his industry, by invading the territories of art, has become art’s most mortal enemy…If photography is allowed to supplement art in some of its functions, it will soon have supplanted or corrupted it altogether…”

Time proved Baudelaire ⅓ right: photography has supplemented our art, but never supplanted or corrupted us. We’ve found new art forms and styles with it, and a photographer is no less an artist than a painter.

But the story doesn’t end here. In the next essay, we’ll find out more about how an under-reported AI copyright case is challenging our fundamental concept of human agency.

Thank you for reading Earthly Fortunes. If you like it, please share it. Subscribe for free to find out more about the Unseen impact of AI on humans and our societies.

I’d love to hear your thoughts about AI and human society! Let me know in the comments, DM me on Twitter or Instagram, or just reply to the email!

There are also claims for trademark and right of publicity violations. But that’s not our focal point here.

50 Shades has a most interesting history of publication and copyright controversies. The book itself though, is completely trash.

I speculate that Getty Images vs Stability AI is a fallout from rights negotiations. But who knows.

The only exception is the CC0 license for works in the public domain.

I’ve been wondering about the implications of AI using “data” (other peoples work) to create writing and images but haven’t seen anything as comprehensive as your essay here Helen! Very interesting, both the history of copyright and the potential implications for the future. Loved the “do you really want to find out” motif too!

Finally getting a chance to catch up on your newsletter, Helen. I loved seeing this after our chat!

I think you do an awesome of breaking down the issue and implications and unpacking what copyright protects. I definitely feel like I have a better sense of what’s going on/what could potentially happen.

I love this warning: “This essay is for information and entertainment purposes only. Take everything I say with a pinch of salt.”

And these lines made me laugh:

“(If next week my Google top results become sponsored ads by Playboy or Penthouse, I’ll know why.)”

“No heirs of St. Matthew would chase you down for a license fee or sue you for copyright infringement.”

Awesome essay, super insightful, and definitely engaging!