This is part 3 of the series A Sea Changed. See part 1 for a storm of salt, part 2 for the fisherman in the desert, part 4 for a T. S. Eliot quote, a theme song by Tom Lehrer, among other things, part 5 for candy and vodka.

Here, we start diving into the broader, higher-order, and unseen consequences of the changed Aral sea.

Happy new year! Here is a Waltz by Johann Strauss II to dance to as we get into 2023.

“All that is gold does not glitter.” — J. R. R. Tolkien

If Tolkien had been traveling with us to Jizzakh, he would have had cotton in mind, when thinking of the kind of gold that does not glitter. Indeed, “white gold” has been the local nickname for cotton for long. Since the American Civil War cut off cotton supply to the Russian Empire in the 1860s, cotton — a water-hungry crop — has blossomed across central Asia, especially in Uzbekistan, a country that is mostly desert.

Cotton planting season had just begun, so the white sea of soft, fluffy fiber balls was still months away. However, the farmers we chatted with were beyond excited. You can’t eat cotton1, you make money with cotton. So said the farmers and croppers. Cotton means livelihood and prosperity to them, and a whole lot more to the world. Cotton alone accounts for ¼ of the world’s textile fiber use, and our lives revolve around it. Every t-shirt, jeans, bath towel, duvet, and makeup remover swab – among many other industrial and commercial things – has cotton. Simply put, cotton is something we could not live without.

Unlike gold, cotton “the white gold” does grow on trees — stalks, to be exactly. There was only one problem: cotton is water-hungry. On average, it takes 2,700 litres of water to produce the cotton needed for one t-shirt, enough for an average adult to drink for 2.5 years2.

For a farmer (as yours truly once was), water comes from two sources: nature, or human force. The first is precipitation: rains, mostly. The second is irrigation: moving water to crops from somewhere else.

There was only one problem: the cotton fields hardly get any water from nature, because of geography. Jizzakh is a major cotton-producing region, and it is 1,100 miles (~1,770 kilometers) from the Indian ocean. That’s the distance between Orlando, FL and Boston, MA, especially in winter. Further, between Indian ocean’s monsoon rains and Jizzakh’s cotton, stand two of the world’s highest mountain ranges.

But for irrigation, geography offered conveniences: two large rivers, Syr and Amu, flow through central Asia, and eventually feed into the Aral sea. The solution was obvious: moving river water from Syr and Amu, to the farmland of white gold.

So it began: on Syr and Amu rivers, in late 1950s and early 1960s, large irrigation projects have been completed3. Dams were built to regulate flood and create reservoirs. Canals were dug to get river water into croplands. Smaller irrigation channels and links followed up across fields, to take their shares of water.

Since then, in the heat of summer, you can see cotton buds grow into blossoms, and blossoms open into colorful pedals, in Jizzakh’s fields.

Beneath the blossoms and between crop rows, river water that traveled more than a hundred miles through canals and channels, were quietly feeding the thirsty plants.

There was only one problem: cotton was so valuable, that its production expanded to 60% of Uzbekistan’s arable land. To maintain this monoculture, fertilizers and pesticides were needed in large doses. On average, for a cotton field the size of an NFL football field, more than 40 pounds (~18 kilograms) of pesticides and 265 pounds (~120 kilograms) of fertilizers were applied, each and every year.

Water secured, soil nutrients provided, and pests killed, cotton buds should bloom in peace then. There was only one problem: the water channels leaked. Before reaching cotton fields, anywhere from ⅓ to ¾ of river water already seeped away, or evaporated in the arid weather. To keep up with booming cotton productions, more water was diverted away from the rivers. Meanwhile, some leaked water, mixed with pesticide and fertilizer run-offs, flew into Aral sea. There, the run-off sediments settled into the seabed, never expecting to be seen again.

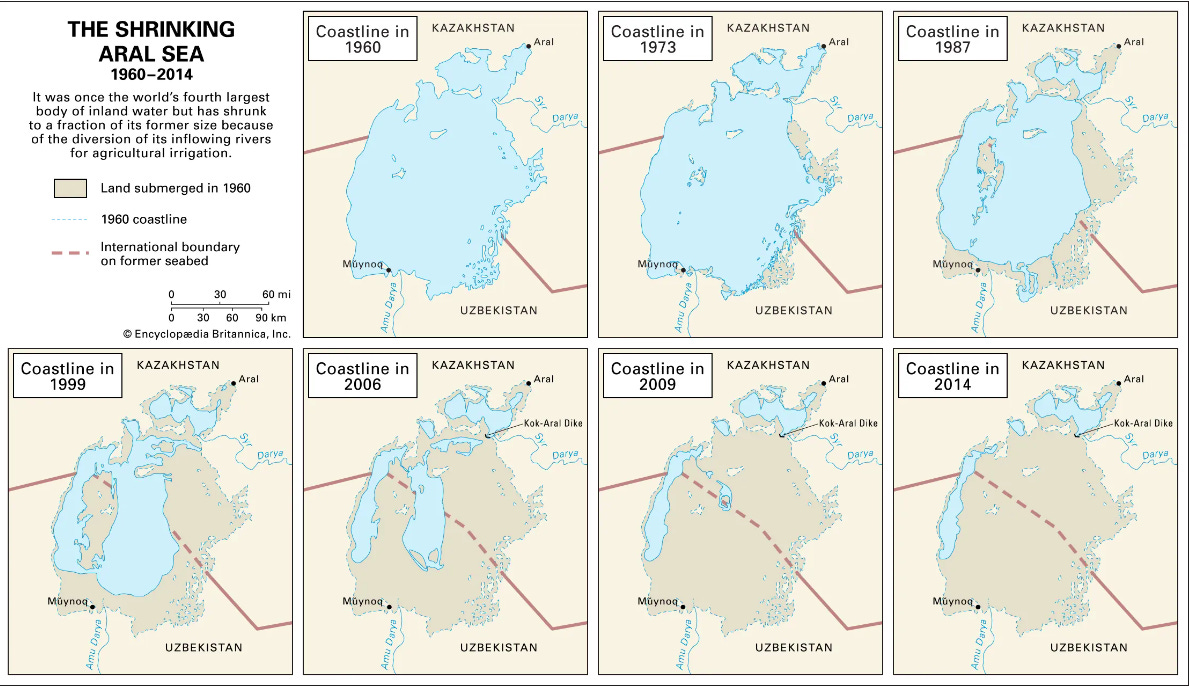

There was only one problem: Aral sea evaporates all the time, but only relies on Syr and Amu rivers for water intake. As cotton productions took away more and more river water, Aral sea started to shrink. Year after year, in less than 50 years, an Ireland-sized lake was reduced to sands, and layers of fertilizer and pesticide sediment.

A sea change followed. With Aral sea gone, local climate turned drier and worse-tempered. The fertilizer and pesticide sediments got swept up in raging salt storms. A ship captain turned into a graveyard keeper in the dunes. Muynak, a buzzing fishing town, was 90%-abandoned. Countless people’s lives and livelihood permanently changed for the worse.

Walking out of Jizzakh’s cotton fields, I wondered if this chain of reactions ever entered into the mind of a planner or an engineer. I still don’t think there was intended malice: after all, since the dawn of agriculture, human has built irrigation systems to survive and thrive in hostile environments. So what went wrong?

Newton’s Third Law states that

Every action has an equal and opposite reaction.

But, in our lives and our societies, every action has a chain of opposite reactions. These reactions are not equal to the action by any means, and they can seem very far-removed from immediate consequences of the initial action. Who would have thought that large-scale cotton production via irrigation could drain a lake as big as Ireland?

Perhaps it’s uncomfortable to think through far-removed — or, in a fancier term, “higher-order” — consequences. Perhaps it’s hard to see through and untangle the interconnected parts in our lives and societies. But we must learn: to think far and wide, to contemplate into higher-order consequences, to see through interconnections in our lives, societies, and our relationships with nature. Because none of us is an island.

And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls;

It tolls for thee.

(John Donne)

Thank you for reading Earthly Fortunes. If you like it, please share it. Subscribe for free to join me on the journey of discovering wider and higher-order impacts .

Let me know your thoughts in an email reply, in the comments or DM me on Twitter or Instagram!

For the most part.

Recommended daily water intake for an average adult is 3 litres. Specific water intake amount depends on gender, activity level, individual physical conditions, etc..

Smaller scaled irrigation projects were built during imperial Russia’s reign, but large-scale constructions happened mostly in the 1950s and 1960s.

Loving the use of repetition in this one, Helen.

Also that Tolkien quote!

"Because none of us is an island." a darling metaphor