Welcome! 😄I’m Helen and here I write about the fortunes that come from the Earth: geography, medieval farming, music, time, and the Unseen.

Here’s a new essay of the series Quid ex Machina, on the Unseen impact of AI (and more broadly, technology) on our societies. See here for the rest of the series.

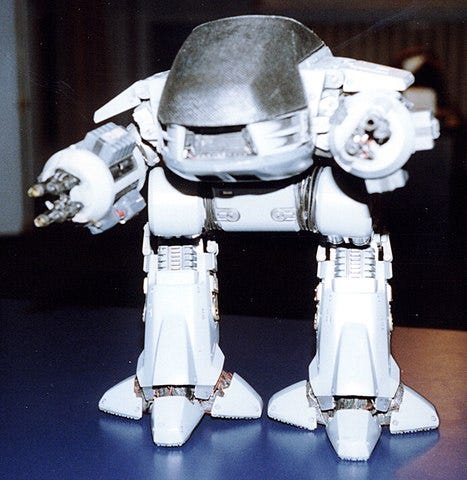

Today’s theme song is the soundtrack of the 1987 movie RoboCop.

[Apologies for delivering this late on a Saturday. My internet wasn't functioning for the most part of the last 24 hours, and I wasn't in a place to borrow other people's internet.]

Many years ago, when Facebook was at its peak before the Cambridge Analytica scandal, I was a student visitor to its headquarter at 1 Hacker Way, Menlo Park, California. I don’t remember much, other than a free lunch, and a recruiter’s passionate speech about a banner that says, Move Fast and Break Things.

I was young but never impressionable, and always spoke my mind. So over lunch, I tried to pry specific answers – instead of vague buzzwords– out of the FB insiders assigned to my student group.

What “things” are we speaking of? I asked. Whose “things” is Facebook breaking? If you break things that are not yours, do you buy them? Do you fix them? What if those broken things can’t be fixed? Do you make new things to replace the things you break?

The diplomatic non-answers flew over my head. But I was intrigued – and mildly alarmed – by the confidence and certainty that FB employees spoke of the “mission, vision, disruption, and innovations” of FB. It reminded me of how sheriffs in Western movies talk about catching robbers and keeping peace in town.

This Western-sheriff-level of supreme self-confidence is not limited to peak-day FB. It is wide-spread among software makers, from rank-and-file employees, to powerful executives and venture capitalists. And this self-confidence is well-placed. Because like sheriffs in Western towns, software makers are the law-givers of our era. In deciding matters of life and death, software encroached on the traditional territory of legal and moral decisions. Want to get your money back from bad actors? A hard fork in the software code will do it, no need for law enforcement at all.

And software doesn’t stop there: it takes up law’s social functions as well. Software now sets arbitrary rules for our lives, demands specific actions from us, and passes judgments about our behaviors. The only difference is that, software runs these social functions at a much faster pace on a bigger scale than good ol’ fashioned law. Think how many reCAPTCHAs are popped in one minute all around the internet to judge if we are human; ironically, no human court of law could make that many decisions in a century.

This phenomenon goes much deeper than the Silicon Valley proverb software is eating the world. Here, software is displacing the world. The grand and trivial laws of our times are being replaced by software and the “business logic” baked into them, but we barely seem to notice this displacement.

Here’s why we don’t notice: because unlike old-school law-makers, software and their makers do not need to seek popular consent, or to obtain authority from any public institution to make up laws and impose these laws on us.

And there is more. When we download apps or tick the “I agree” checkbox for terms and conditions, we don’t think about the arbitrary rules they may impose, or how they may change our behaviors. But when we pick our law-makers, these are the questions we often ask in public. Instead, we tick the boxes in private, think about the conveniences offered by the software, and almost never ask questions – like a hasty shopper in a liquor store at 10:59pm on a Friday.

Put it another way: software has also replaced the public relationships between law-makers and their constituents, and set in place a private relationship between a vendor and its customers.

By default, public relationships are open to public scrutiny, while private relationships are not. But software runs at a massive scale, and forms a private relationship with each of its many customers. At what point, does this vast collection of private relationships become a public relationship? And despite the absence of popular and institutional consent, software makers still subject us to the petty laws they make up. So what is the source of their law-making authority? Who gave them the power?

In the next essay, I will lay out a brief history — a short genealogy, if you will — on the source of authority in law-making. How did we come to this place, where software makes laws that govern our lives? The answer may surprise you, but I think the arc of history speaks loud and clear.

Thank you for reading Earthly Fortunes! Like it? Please share it! 😄 Subscribe for more earthly fortunes: geography, music, time, medieval farming, and the Unseen.

I’d love to hear your thoughts! Comment below, DM me on Twitter or Instagram, or reply to the email! Anything you send me, I’ll read it 😄

Oof yes I’m looking forward to this series! I love imagining a young Helen at FB HQ asking the tough questions.

Loved this, Helen. But that's no news! You're always so capable of surfacing ideas and themes and details that I never thought about. So grateful to be able to read you! :)